Al-Jahiz – Real Father of Evolutionary Biology

- Al-Jahiz described three mechanisms of evolution. These are, Struggle for Existence, Transformation of species into each other, and Environmental Factors

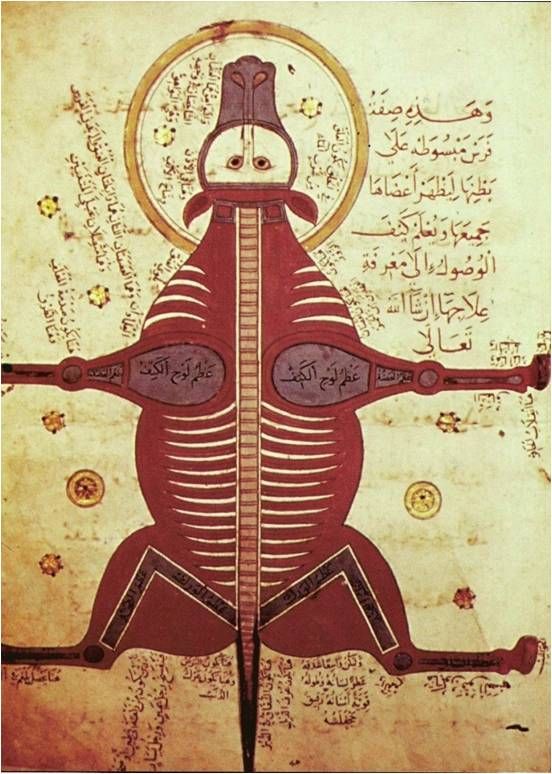

Al-Jahiz, an Arab polymath who lived during the Islamic Golden Age, is sometimes referred to as a forerunner in the development of evolutionary thought. Born in Basra in 776 AD, he was a prolific writer on a wide range of subjects, including Arabic literature, zoology, poetry, lexicography, and more. His most famous work, “Kitab al-Hayawan” (The Book of Animals), is where he discusses various aspects that resonate with some of the ideas later formalized in the theory of evolution.

Say (O Muhammad): Travel in the land and see how He originated creation, then Allah bringeth forth the later creation. Lo! Allah is Able to do all things.

Quran 29:20

Al-Jahiz and the Precepts of Evolutionary Theory:

- Observations on Animal Adaptation: Al-Jahiz observed how environmental factors could influence animals’ chances of survival. He noted that animals that could adapt to different circumstances had better survival prospects.

- Food Chains and Environmental Influence: He described food chains and how environmental factors and resources influence species’ development and behavior.

- Competition and Survival: One of his key insights was the concept of the struggle for existence. Al-Jahiz recognized that competition within and between species was a significant driving force of survival and adaptation.

- Inter-species Relationships: He also discussed how interactions between different species could impact their development and survival, touching upon aspects of symbiosis and mutualism.

Al-Jahiz’s contributions, however, are significant in illustrating the rich intellectual tradition of the Islamic Golden Age and showing that many ideas we consider modern have ancient roots and precursors. His work indicates an early understanding of some aspects of what would later become ecological and evolutionary science.

He created the heavens and the earth with truth, and He formed you, then made goodly your forms, and to Him is the ultimate resort.

Qur’an 64:3

Influence Of Al-Jahiz’s Works On European Scientists

As for the influence of al-Jahiz on European thinkers, it has become the subject of two main studies: “Der Darwinismus im X und XIX Jahrhundert” of Fr. Dieterici (Leipzig, 1878) and “Darwinistisches bei Gahiz” of E. Wiedemann (sitzungsbericht der physikalisch-medizinischen Sozietaet in Erlangen, 47, 1915). Previous to me, they found a great similarity between al-Jahiz and Darwin. Indeed, Darwin and his precursors took up the theory of al-Jahiz as the base for the essentiality of their evolutionary theories, and they formulated it in a more scientific way in the context of eighteenth and nineteenth centuries development of science. Perhaps the only main difference between al-Jahiz’s theory and modern theory is in ideology: al-Jahiz’s theory is theologic and more transcendental in this sense that he accepts that the first cause of evolution in living organisms is God and that the other factors are secondary; while Lamarck, Darwin and others’ evolution is more immanent and materialistic. Although the mechanistic explanations of the theories are more or less the same, Darwin and other modern scientists differ from al-Jahiz and other Muslim writers in ideological interpretation of the theory.

Though a great majority of people, regardless of their religion, consider Darwin as the originator of the idea of evolution, Shanavas reminds us that Darwin (1809-1882) and his grandfather Erasmus Darwin were influenced by the work of Muslim scientists who lived centuries before them. For instance, Dr. Shanavas quotes from John William Draper (1812-1883), first president of American Chemical Society, a contemporary of Darwin, and a former president of New York University summarizes the deliberately induced academic amnesia in the West. Draper acknowledges the fact that Muslims described the theory of evolution in their schools centuries before the West did:

“I have to deplore the systematic manner in which the literature of Europe has contrived to put out of sight our scientific obligations to the Muhammadans. Surely they cannot be much longer hidden. Injustice founded on religious rancor and national conceit cannot be perpetuated forever.”(Draper, John William. The Intellectual Development of Europe, p. 42.) *please refer to full article @ http://www.19.org/books/islamic-theory-of-evolution-shanavas/)

Read more: https://newsrescue.com/muslim-quran-predate-darwin-evolution-theory/#ixzz4HzNz97SW

How Was Jahiz’s idea transmitted to the Europeans?

Al-Jahiz and other evolutionist Muslim thinkers influenced Darwin and his predecessors in several ways. Before the flourishing of C. Linnaeus (1707-1778), Buffon (1707-1788), E. Darwin (1731-1802),J. B. Lamarck (1744-1829), and Ch. Darwin (1809-1882), and long before the rise of the school of Natural Philosophy in Germany, al-Jahiz and others were known to Europeans through the translation of their own works and studies on them by Europeans. For example, al-Damiri’s book Hayat al-Hayawan was partially translated into Latin by a Jew, called Abraham Echellensis (d. Italy 1664) and published in Paris in 1617. This book contains many passages taken from al-Jahiz’s Kitab al-Hayawan. Al-Nuwayri’s JVihaya was studied by D’Herbelot (1625—1695) in his Bibliotheca Orientalis, and later byJ. Heyman (?—1737). Ibn Tufayl’s Hay Ibn raqzan, which contains the philosophy of evolution, was first published by Edward Pocockes, Sr. (1604-1690), together with a Latin translation published by Edward ~Pococke, Jr. (1648-1727) in Oxford in 1671 (second edition, Oxford, 1700) “20”.

Zakariyya’ al-Qazwini’s cosmography, ‘Aja’ ib al-Makhluqat was published by F. Wustenfeld in 2 volumes in Gottingen in 1848-49; and Kitab Talkhis al-A thar of Bakuwi, a summary of al-Qazwini’s book was translated into French and published by De Guignes in Paris, in 1789 “21”. In fact, his book also contains many ideas from al-Jahiz. And A. L. de Chezy translated al-Qazwini’ s ‘Aja’ib, and his translation was published in 1806 (first publication) by S. de Sacy, in his Chresiomathie A rabe. There is no doubt that the great evolutionist sufi, Mawlana, had already influenced Goethe, who called him “a Darwinian before Darwin” “22” his theory of metamorphosis has profoundly affected the development of biology. In any case, Islamic zoology penetrated the West as early as the seventeenth century “23”. Some Europeans knew Arabic and they could read directly from the Muslim scientists’ books; for example, Darwin was himself initiated into Islamic culture in Cambridge under a jewish orientalist called Samuel Lee “24”. We think that what we have said can show Muslim influence upon Europeans. Some further comparative study can be undertaken in this subject, in order to bring to light the influence of Muslim evolutionist thinkers upon the Europeans and the transmission of their ideas to the West.

Al-Jahiz’s theory of evolution was something very new in the history of science, and there was nothing written previous to it. Although Greek philosophers like Empedocles and Aristotle spoke of the change in Nature, in plants and animals, they never made the first steps on the field of the future theory of evolution of the Muslims. Their concept of change was only a concept of simple change and motion, nothing more than that. And by the concept of change, they never designed explicitly or implicitly a concept of evolution: “The World of Nature is thus for Aristotle, a world of self-moving thing, as it is for the Ionians and for Plato. Nature as such is process, growth, change. This process is a development, i.e. the changing takes successive forms, a, b, y, . . . in which each is the potentiality of its successor, but it is not what we call ‘evolution’, because for Aristotle, the kinds of change and of structure exhibited in the world of nature form an eternal repertory, and the items in the repertory are related logically, not temporally, among themselves”25″”.

References

1) Pellat (Ch.), “Al-Dlahiz”, in RI2, vol. II, p. 385.

2) Ibn ‘Asakir, MMIJ, IX, pp. 203—217.

3) Khaiib Baghdadi, XII, pp. 212-222.

4) Sarton (G.), Iniroduciion in ihe Hisiorp of Science, vol. I, Washington, 1927, p. 597.

5) Pellat (Ch.), “Gahiziana”, in Arabica, 1956/2; cf Brockelmann (C.), GAL, SI., 241ff

6) The Book of .4niinals was published in 7 volumes, in Cairo, 1323—1324.

7) Sarton says: “His most important work is The Book oj.-Inimals, a very discursive compilation, the purpose of which is theological and folkloric, rather than scientific , Sarton, op. cii., p. 597. Sarton’sjudgement is not true; indeed, many of the knowledges given in the 1)00k are the result of his personal observation and his experiences, as al-Jahiz himself says in several chapters.

8) Asin Palacios (M.), “El ‘Libro de los Animales’ deJahiz”, in isi.’;, vol. 14 1930, p. 21.

9) Some parts of’ his book are published by R. Geyer in Wien, in 1887; and by A. Haffner in Wien, in 1895—1896; the book on the creation of man is still unpublished.

10) It is very interesting to notice that a summary of’ al-Damiri’s and other Muslim scientists’ books was translated into Latin by Abraham Echellensis (d. Italy 1664) and was published under the title “Dc Proprietatibus et Virtutibus Medicis Animalium” in Paris, in 1617. So, that is to say, sometime before the appearance ofbarwin’s precursors, such as F. Redi (1626—1698), C. Linnaeus (1707—1778), Buflon (1707—1788), Lamarck (1744—1829). the idea of evolution of Muslims was penetrated in West and this explains why the first evolutionists came from France. See Mieli (A.), La Science .1 robe ei Son Role dan l’Et’oluiion Scienijfique Mondiale, Leiden, Brill, 1938, pp. 263-264, n. 3; and extracts have been translated into French by A.J. Silvestre dc Sacy, Oppianos II, Strasbourg, 1787; see Sarton (G.), Vol. III, Part II, p. 1641. 11) Pella (Ch.), ‘Al-Djahiz”, op. cii., p. 386; cf Sarton, op. cii., p. 597.

12) Al-Jahiz, Kiiab al-Ha vawan, Vol. I, Cairo, 1909, p. 13, and see also different chapters of the volumes.

13) ldem., Vol. VI, pp. 133—34; and there are many passages in different volumes illustrating the struggle for existence. See VI, 139; VII, 47, 80. 14. ldem., vol. VII, pp. 47-48.

15) According to some opinions, this original form of animal was lost because of earthquakes and floods. See al-Jahiz, op. cit., vol. IV, p. 24; cf vol. VII, p. 77.

16) ldem, vol. IV, p. 23.

17) ldem., vol. IV, pp. 24-25; c1 vol. VI, pp. 24-26.

18) I think al-Maskh is a kind of ape; see Vol. IV, p. 24. And do not confuse al-Maskh with al-Miskh.

19) ldem., Vol. IV, p. 24; and cf vol. IV, pp. 25-27.

20) See Sarton (0.), op. cii., vol. II, Part 2, pp. 354—355.

21) Mieli (A.), op. cii., p. 152.

22) Cassirer (E.), The Problem of Knowledge, translated by W. H. Woglom and Ch. W. Hendel, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1950, p. 137.

23) Sarton (G.), op. cii., vol. III, part 2, p. 1641.

24) See Darwin (Sir F.), The Life and Letters of’ Charles Darwin, vol. I, London, 1887, p. 289. Samuel Lee (1783-1852), of Queen’s, was professor of Arabic and Hebrew. In 1821, he issued a “Sylloge Librorum Orientalium”. In 1829, he translated “The Travel of Ibn Battuta”, see The Dictionary of National Biography, vol. XI, London, 1917, pp. 819-820.

25) Collingwood (R. C.), The Idea of’ Nature, Oxford, 1945, p. 82.

The Islamic Quarterly, London

Third Quarter 1983